After nearly three hours flying at 140 mph and several serious discussions about "shouldn't we turn back now?" we suddenly broke out of the overcast and all considerations left us other than completing this long interception. It was now late night, without moonlight, but as we closed in, Ab gave me a "tally ho" at a range of 500 feet. We made a careful identification. Another "lily," this time noting the exceptionally high vertical stabilizer and a break in the silhouette along the bottom on the fuselage line near the tail.

Also, this time Ab put a little more space between us and the target before we opened fire. Neither of us was prepared for the super spectacular that took place. Hollywood couldn't have equaled it. The enemy plane instantly burst into flames, lighting and backlighting the billowing clouds of the overcast still all around us. At the same time, a heavy plume of black smoke poured out of the stricken plane, contrasting with the light clouds and looking like huge, sooty entrails. Then, as it continued its plunge, there were explosions tearing parts of the plane off as the bomb load, at intervals, blew up.

Magnesium is an ultra-lightweight metal that burns with fierce intensity. They made railroad flares out of magnesium. The Japanese also made the "Lily" bomber out of this material, accounting for the brilliant neon fireball. Still, most of the wreckage hit the ground in one flaming piece that instantly

extinguished

itself. It was then that we noticed we were at the very edge of

the city of Nanchang. A lot of lights were showing here and

there. We wondered if our fireworks display was as dramatic seen

from the ground as it had been from the air.

extinguished

itself. It was then that we noticed we were at the very edge of

the city of Nanchang. A lot of lights were showing here and

there. We wondered if our fireworks display was as dramatic seen

from the ground as it had been from the air. We didn't hang around at all, but turned back toward Laohokow. The return flight problems that we had considered for the past couple of hours were now our paramount concern, and there were difficulties. Extra fuel had been used while we maneuvered during the interception. We were at our maximum operating range away from Laohokow. There was no margin for navigational error, and no fuel reserve we could be sure of. Ab reduced power until we were barely flying on the leanest possible mixture settings. Our air speed was probably 125 mph, which would make for a long 3-1/2 hour flight home.

The navigation problems were mine. We were proceeding on dead reckoning, which normally would be helped along by visual references -- a river, a village, a mountain, a road, something. But we were back in the overcast and radar images of these kinds of terrain features couldn't always be relied on. Besides, our charts were full of gross inaccuracies, like a lake where a mountain was supposed to be. As bad that that.

Our best bet was to fly an exact reciprocal course to the one we flew while we were following our bogie. So, we took the northwest heading and hoped. Winds aloft were the biggest question. A cross wind of only 5 mph would drift us over 15 miles off course by the time we reached Laohokow. In the overcast, with a low ceiling and no way of knowing whether we had been blown east or west, we could miss Laohokow entirely.

There was also a third problem -- remaining patient in the management of the first two problems. I kept the radar on in a navigational model, scanning the terrain ahead with a sectional chart in my lap, trying to establish just one flickering radar image as being a positive landmark shown on the chart. For three hours I was never sure once, not even close to being sure. We talked about maybe we ought to change heading -- a westerly course would likely take us into friendly territory if we had to bail out. Laohokow was all but surrounded by the enemy and a bailout in that vicinity would probably land us in Japanese hands. But we stayed on the reciprocal heading. We were committed.

After two hours we tried to reach Blackie every ten minutes or so, but there was no response. After three hours, we were sweating it out. Fuel was now very low -- we had begun alternating tanks to run each one dry. There was still fuel in the reserve tanks, but maybe only 20 minutes' worth. The radar was still giving me great pictures of unfamiliar things, but suddenly what I was looking at wasn't entirely unfamiliar. Maybe it was a hunch, but there was a confluence of small rivers just west of Laohokow. This could be what I had on my radarscope. We decided to let down through the overcast. Using radar as a terrain altimeter, we broke out of the overcast at 1,000 feet. The rivers were now indeed familiar. Laohokow should be just a few miles to the east. We weren't absolutely sure of all of this, until Blackie finally answered our call. We were all ecstatic, tremendously relieved, and we were back on the ground ten minutes later. We were all too tired to celebrate getting home, the victory or anything. We secured the plane and fell into our bedrolls at about 4:30 a.m.

We couldn't have known this at the time, but our mission that night fulfilled the primary mission of the night fighter squadrons in China. Our tracking that Japanese bomber for hours in an overcast, and shooting him down within sight of his home base, was so demoralizing to the Japanese bomber crews that they never attempted another night bombing raid in China. From the Japanese pilot's viewpoint, what had happened must have been terrifying, almost supernatural.

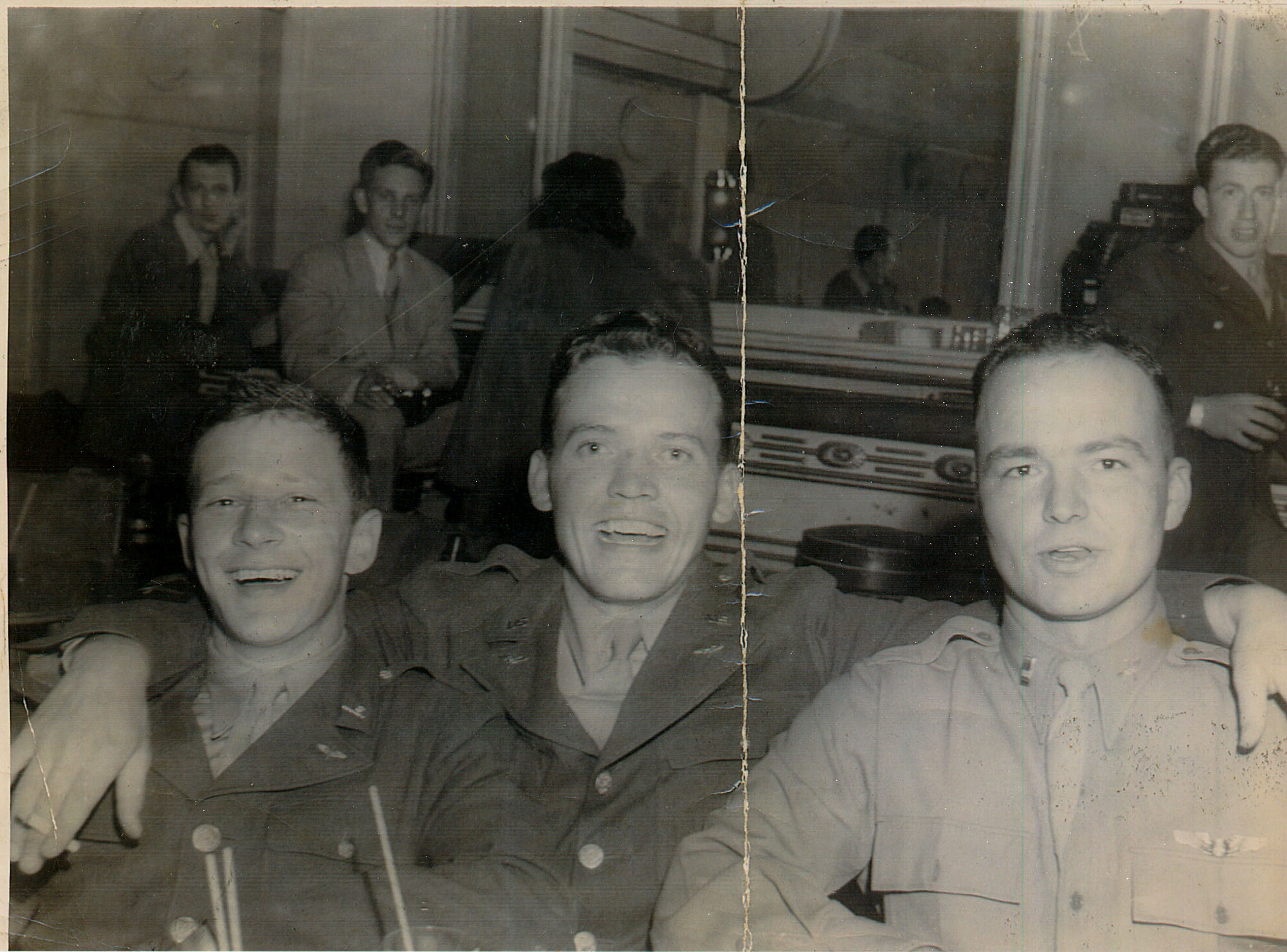

Photo above: Smith and two service pals in a moment of relaxation.